Why Housing Is So Expensive in San Diego?

Think about the barista that makes your coffee, your children’s teacher, or the person experiencing homelessness in your neighborhood. In San Diego, their access to affordable housing is quickly slipping away—and it might be for you too! This reality is backed by staggering numbers. In San Diego:

Affordable Rental Housing is Unavailable: According to SANDAG’s reporting, between 2021 and 2024, the City of San Diego has permitted 4,781 affordable housing units compared to 24,122 market-rate units, far behind the target needed by 2029 (only 7.5%). Marketrate housing is on track to meet the target (24,122/55%).

SANDAG RHNA 6th Cycle 2021-2029

Homeownership is Expensive: The median home price is now $1.025 million—higher than the Los Angeles metropolitan area.

Homeownership is Largely Unattainable: Only 12 of every 100 families can afford a median-priced home.

These numbers are alarming, but how did we get here? We provide four reasons why housing markets throughout the U.S.—including San Diego—are so expensive.

Our Housing System Is Flawed

The U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights asserts housing as a human right akin to food or drinkable water access. Yet, in the U.S., housing is often an investment. Americans buy homes not only for shelter, but also to build generational wealth. Because we build wealth through homeownership, we are incentivized to sell housing at market peaks to secure the highest possible price. While we might individually build wealth through market value increases, the collective impact is devastating for people experiencing homelessness, marginalized communities, lower-income households, and increasingly, the middle class. The person buying or renting housing puts money toward an unaffordable product. Wealth building relying on property values leads to housing affordability, an inherent outcome of the current U.S. housing system.

Supply Will Not Solve Our Problem

You have probably heard that we can lower rent and mortgage costs by building more housing. However, the idea of supply and demand that informs housing policy decisions is rooted in theoretical assumptions that do not exist in the real world.

For starters, land is a limited gift from nature. Additionally, the theory of supply and demand assumes that (a) all people desire the same type of housing, (b) the supply of housing is homogenous—as if building single-family housing could satisfy demand for multi-family—(c) renters/buyers have all the information needed to make cost-effective choices, (d) no external effects influence housing markets, (e) no monopolies, oligopolies, or collusion exist in housing markets, and more. The latter was recently proven false in the Department of Justice’s case against the RealPage application, where landlords were found to be collectively acting as a monopoly by strategically keeping rental homes vacant to fix rents at unaffordable prices and obtain tax incentives. Moreover, the theory claims that market reaches equilibrium where supply equals demand but supply very rarely equals demand in markets. In reality, supply and demand does not operate as it does in introductory economics textbooks. There are multiple market examples of rents and mortgages increasing alongside housing supply increases, and even when markets see decreases in rents and mortgages, they are minimal. When policymakers and advocates call for increased housing supply, a logical response is to ask, “Supply of what kind of housing and for whom?”

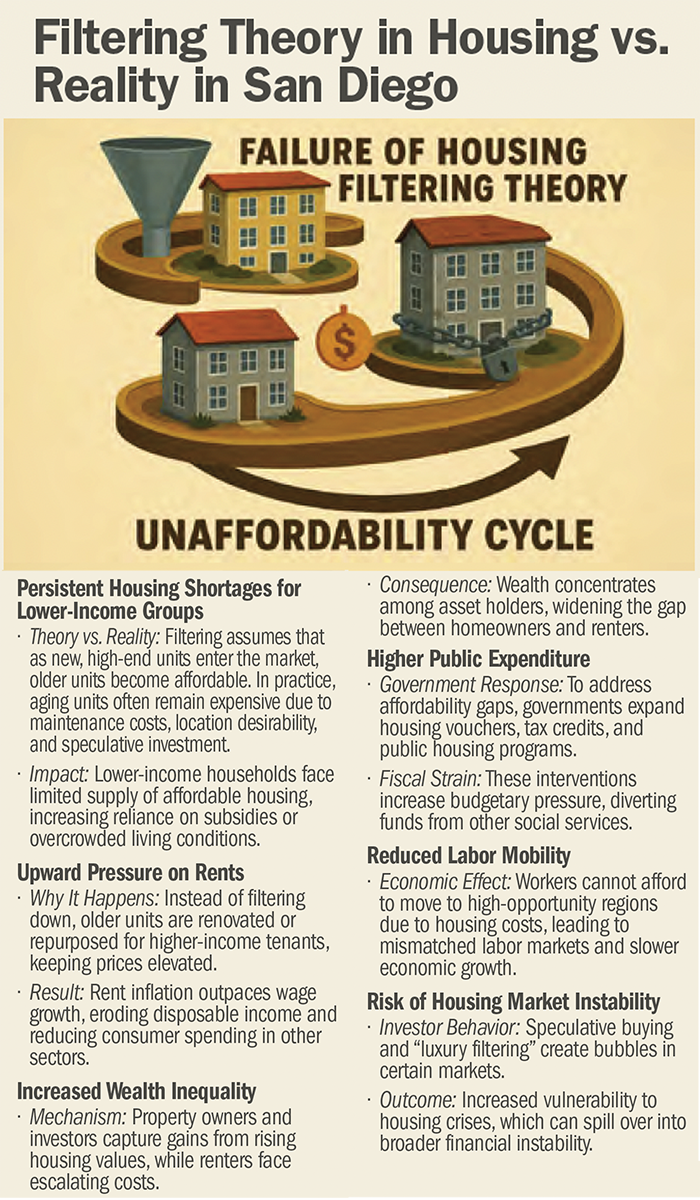

Increased Supply Does Not Trickle Affordability Down

Another longstanding theory influencing housing policy is the idea of filtering or moving chains (see sidebar on next page). The theory asserts that construction of new market-rate or luxury units will trickle down affordability for lower income people. This idea, that higher-income people moving into new housing will leave lower cost housing for others does not work in the real world! As mentioned above, people selling housing seek the highest prices possible: higher-income people afford new market-rate or luxury units by capitalizing on their current unit’s inflation. Instead of filtering affordable housing down to lower-income people, the cycle of unaffordability continues. This issue is more destructive when new buyers are powerful corporations who soak up supply and rent units at exorbitant prices to make a profit.

Federal Housing Policy Has Not Solved Our Problem

Federal housing policies do not solve the problem but rather reinforce it. Our dominant federal policies are direct descendants of the undermining and destroying of permanently affordable, public housing. They prop up the private housing market, which incentivizes property owners to profit from increasingly unaffordable housing. For instance, the primary avenue for affordable housing production in the U.S. is Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC). LIHTC provides tax credits to developers to produce a small percentage (10-20%) of affordable units in new housing developments. However, those units must only remain affordable for 15-55 years, after which they can be converted to market rate rental units: we are subsidizing housing that is not permanently affordable.

Furthermore, developers often recuperate losses from affordable units by increasing rents of remaining market rate units. The affordability of some residents is guaranteed through the unaffordable housing of others! Current federal policies not only subsidize private market actors, but also inadvertently pass on costs of affordability to middle class residents. Development companies are subsidized while the costs of the market are socialized.

Are There Other Solutions?

There are alternative models circulating in housing policy. Community wealth building housing models—such as community land trusts (CLTs), limited equity housing cooperatives (LEHCs), permanent real estate cooperatives, and resident owned communities (ROCs)—help to address inherent problems in our current system by producing permanently affordable housing, allowing low-income homeownership, countering displacement and gentrification through cooperative ownership, and democratizing decision-making. These models don’t encourage wealth building at the expense of affordable housing for others but instead build wealth through housing affordability, as every dollar not spent on housing can be saved or invested in our communities.

At the moment, two CLTs—Avanzando San Ysidro CLT and Tierras Indígenas CLT—three LEHCs—Orange Place, Eucalyptus View, and 15th Avenue Cooperative—and at least forty ROCs exist in the San Diego region.

The San Diego Community Wealth Building Coalition (SD CWB) is currently pushing a resolution for the City of San Diego to support and expand these models of housing. If you would like to learn more, look out for future articles and feel free to reach out to us at the SD CWB Coalition at cwbsandiego@gmail.com.