What Future Do We Want for University Heights?

Since its founding in 1888, University Heights has undergone several periods of growth caused by a variety of factors, including transportation, availability of a reliable water system, the economy, and city planning policy. Housing in University Heights has evolved from sparse single-family homes, cottages, and bungalows to a wide variety of housing types, including duplexes, bungalow and cottage courts, and apartments.

Infill development over the last 50-plus years has generally replaced older housing stock with multi-family housing units, gradually changing the historic fabric of University Heights.

As the City again incentivizes infill development in San Diego’s “first-ring” neighborhoods, our community faces even more losses of potentially historic resources and Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing (NOAH), displacement of current residents, environmental impacts, added stress to inadequate, aging infrastructure, and reduced quality of life.

It’s time to think about what our community wants for the future of University Heights.

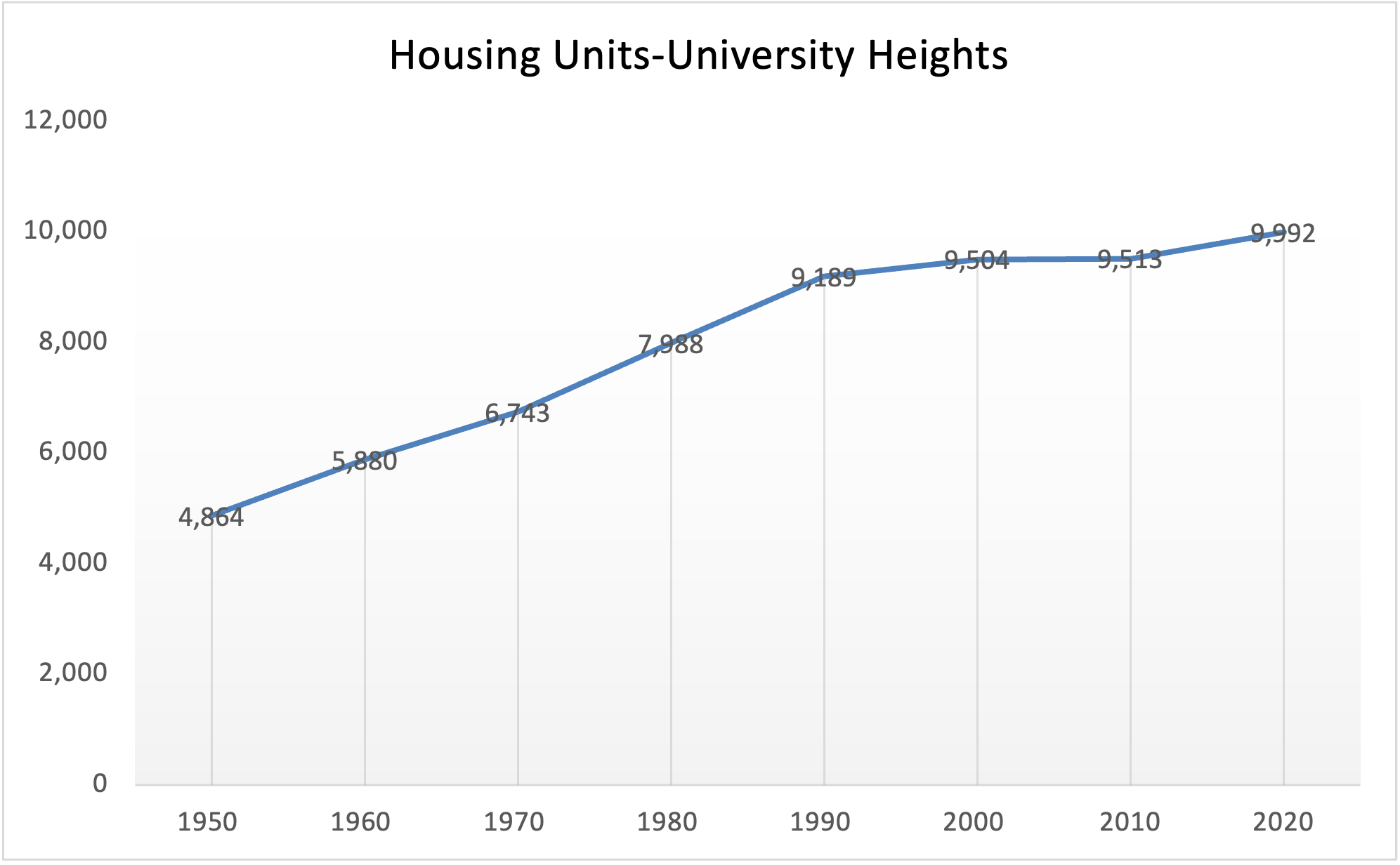

Housing Doubled in University Heights from 1950 to 2020

According to the U.S. Census, the number of housing units in University Heights more than doubled from 4,864 in 1950 to 9,992 in 2020. Of these, 72% are multi-family units and 28% are single-family.

The replacement of single-family housing with multi-family units in University Heights began in 1967 when the City Council adopted San Diego’s first Progress Guide and General Plan. The plan projected a 20% increase in housing units in central San Diego between 1964 and 1985.

The older, more established “first-ring” suburbs of the city, including University Heights, were up-zoned (meaning zoning laws were modified to allow for higher density development) and targeted for infill housing projects, generally resulting in the removal of older building stock. According to the U.S. Census, the number of housing units in University Heights grew by 36% from 1970 to 1990, almost double the city’s goal of 20%.

Housing growth then leveled off and grew by only about 9% from 1990 to 2020.

State Mandates 20% Increase in San Diego Housing by 2029

The California Department of Housing and Community Development has mandated that the city of San Diego build another 108,036 housing units from 2021 to 2029. Of these, 64,199 units (almost 60%) must be deed-restricted units affordable to Very-Low-, Low-, and Moderate-Income households. This represents a 20% increase over the 530,000 housing units in the city as of the 2020 Census.

As of 2024, the city of San Diego has achieved 41% of the state’s goal for total building permits (44,505), but only 7.4% of the state’s goal for deed-restricted affordable units (4,781), according to the California Department of Housing and Community Development.

Since 2020, at least 1,300 units have been completed or are planned in University Heights. This represents a 13% increase over the number of housing units in 2020 (9,992), indicating that our community is well on track to meet the state’s goal of a 20% increase by 2029.

Of these 1,300 new units in University Heights, less than 10% are deed- restricted affordable units. The vast majority are studio, one-, and two-bedroom market-rate, rental units with rents ranging from $2,350 to $5,270. Some of the affordable units, like those affiliated with the Winslow, are located off site at an unspecified location.

Complete Communities Program Incentivizes Overproduction of Market-Rate Units

The city has adopted several new building policies since 2020 to incentivize the production of affordable units. One of these is the Complete Communities Housing Solutions program (CCHS), which incentivizes builders to overproduce market-rate rental units to subsidize a few affordable units.

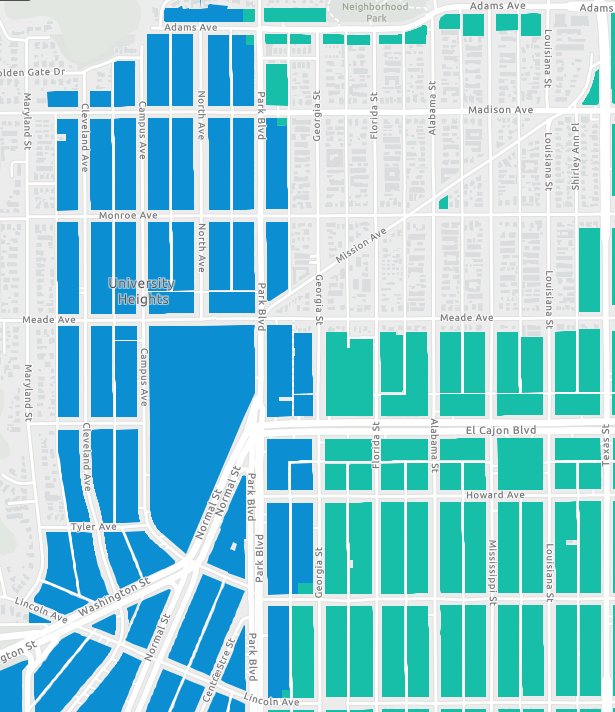

The CCHS program allows for the construction of multi-story buildings up to eight floors without off-street parking within a Transit Priority Area (which includes virtually all of University Heights) if the site is zoned for at least 20 dwelling units per acre, and the project includes the required number of deed-restricted affordable units.

As shown in the map below, the areas in blue and green are eligible for the CCHS incentive program:

According to the city of San Diego’s 2024 Annual Report on Homes, of the 1,131 units permitted citywide in 2023 under the CCHS program, only 10% are affordable to Very-Low-, Low-, and Moderate-Income households, and the vast majority are for rent, not for purchase.

Complete Communities Program Is Inefficient and Unsustainable for Older Neighborhoods

The city’s market-based approach to increasing the number of affordable units is inefficient, destructive, and unsustainable for our older communities with limited and aging infrastructure. By contrast, the San Diego Unified School District is planning for at least 500 units on the Brucker site at 4100 Normal Street, all of which will be affordable and restricted to district employees. The school district is also planning to provide some community open space and park space on the Brucker site.

While the higher, denser infill allowed by the CCHS program makes more sense along major transit corridors like El Cajon Blvd. and Park Blvd. (south of El Cajon Blvd.), it destroys low-profile neighborhood streets in established communities like University Heights.

First-ring neighborhoods like University Heights are targeted for infill because of multi-family zoning, and proximity to both transit and to UCSD Medical Center. However, no consideration is given to the ability of the infrastructure and services—such as schools, parks, libraries, and streets—to absorb a significant increase in housing units and population.

Costs of Aggressive City Housing Policy

Two homes built in the early 20th century have already been demolished since 2020 to make way for CCHS projects in University Heights, and an application has been filed to demolish a third home built in 1890. In addition, one LGBTQ landmark was demolished in 2015 to make way for the BLVD North Park apartment complex.

These single-family homes also represent a lost opportunity to create more “missing middle housing” for a family willing to rehabilitate an older property to live in a safe neighborhood with good schools and close to employment centers. The proliferation of small, market-rate, rental apartments built in University Heights since 2020 simply does not provide sufficient space for a growing family or the chance to build equity.

What Future Do We Want for University Heights?

Over the past 50-plus years, University Heights has accepted more than its fair share of new housing and is on track to meet the state’s housing goal of 20% more by 2029.

The city is now pushing for another 20% increase in housing, targeting first-ring neighborhoods like University Heights. Developers are reaching further into our older neighborhoods to seek infill opportunities, typically on multi-family zoned lots that have an older, single-family home.

This approach is unsustainable inequitable, and taking an increasing toll on our older neighborhoods. As a community, it’s time for us to think about what we want for the future of University Heights.

For more information, visit www.uhhs-uhcdc.org/blog.